507 West Adams Street

PLEASE ALSO SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

PLEASE ALSO SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO ADAMS BOULEVARD, CLICK HERE

- Built in 1890 on a parcel comprised of Lots 33 and 34 of the Longstreet Tract by John M. Menefee; sold on June 12 of that year to Arkansas-born civil engineer George West Hughes

- John Menefee had come to Los Angeles in 1885 from Mexico, Missouri, where, according to a local history published the year before, he was a dealer in undertaker's goods, including coffins, as well as a manufacturer of household furniture for the quick. Menefee was indecisive about settling permanently in California, buying 507's building site on August 21, 1889, for $3,950, building the large turreted house, and living there only briefly before selling to Hughes and returning to his home state; back in Los Angeles the next year, he built another house at 2413 South Grand Avenue—near the one he'd recently sold—and died in the city in 1898

- George West Hughes had been building railroads in his native state when his health suffered in 1885; boom-era Los Angeles offered the chance for better health as well as opportunity for a still-ambitious man. Settling with his family on Bunker Hill—at its peak before the districts developing down toward U.S.C. (opened in 1880) began to lure its rich away—Hughes followed the well-heeled to West Adams Street, nearly rural before its streets were macadamized but now being suburbanized with curbs and sidewalks. To keep himself busy in his new locale, Hughes turned to banking. Perhaps seeking a change in his domestic arrangements after his youngest son, 27-year-old George Reavis Hughes, an attorney, died suddenly in Little Rock in February 1889, he seized the moment to acquire a brand-new house and made an offer the waffling Menefee couldn't refuse

- The Times reported on May 31, 1890, that Menefee had petitioned the city to have six-foot sidewalks installed on the north side of Adams between Grand and Figueroa

- On July 13, 1890, both the Times and the Herald reported Menefee's sale of 507 to Hughes for $16,000 the day before. To celebrate their new acquisition, the elder of the two surviving Hughes sons, Walter, a graduate of the University of Virginia and of Harvard Law—his dead brother had followed the same path—was married in the house on July 9. Walter and his wife, née Rosa Bein, moved into 507 after their honeymoon

- The middle Hughes son, Henry West Hughes, was also a graduate of the University of Virginia. Continuing his education at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, he was practicing medicine in Los Angeles and living at 507. Known professionally as Dr. West Hughes and personally as Harry, he was given to advertising his services in the classifieds of local newspapers

- West Hughes married Cora Jarvis of Louisville in that city on June 8, 1892; after their honeymoon, they moved into 507. In 1899, the couple built a house one block north at Flower and 23rd streets

- The Herald of August 15, 1893, reported that George Hughes was protesting the proposed opening of Flower Street through from the business district; at the time, the thoroughfare ran piecemeal southward. (Flower would eventually be completed as a major direct southerly route, in 1932 being rammed through the houses across Adams from 507; 20 years after that, the Harbor Freeway invaded the neighborhood

- It is not clear as to whether Lot 31—which contained 507's carriage house—and Lot 32—which completed the parcel to the alley running north from Adams, parallel to Flower and Figueroa—were added to the parcel by Menefee or Hughes

- Walter J. Hughes died at 507 West Adams on June 12, 1895, age 39, leaving his wife and three children. The funeral was held at 507 two days later

- George West Hughes died at 507 West Adams on March 25, 1900, age 67. The funeral was held at 507 two days later

- Rosa Hughes's widowed mother, Lizzie Gibson Bein, arrived in Los Angeles to live at 507 by June 1900

- Martha Butler Hughes, George West Hughes's widow, died at 507 West Adams on May 31, 1912, age 77

- Rosa Hughes and Lizzie Bein were last listed at 507 in the the Los Angeles city directory's 1916 issue

- It is unclear as to whether Rosa Hughes retained ownership of 507 to rent herself or whether she sold it to a party who did; by 1917, a boys' boarding school, The Swiss College of America, was occupying the house, having moved from a downtown building

- The Swiss College of America, which advertised itself variously, was headed by Camillus J. Williams; by late 1919, the school had relocated and 507's rooms were being let by various parties including a dentist and a musician offering instruction

- In the 1920 Federal census, Frank S. Pedregal was renting 507; living with him were two teen-age boys who were attending the Williams International School—formerly the Swiss College—now located in another old house, this one at 659 West 35th Street. (The school was short-lived at its new address and the U.S.C. School of Architecture's original building rose on the site in 1925)

- Another renter, Mrs. Louise Griffith, was advertising furnished rooms at 507 during 1921 and 1922

- By 1923, 507 West Adams Street—the upgrade to "Boulevard" was not yet official—had been acquired by the local Catholic diocese, which had recently been renamed the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles–San Diego from that of Monterey–Los Angeles

- The bishop's name, John J. Cantwell, appears on the demolition permit for 507 West Adams issued by the Department of Buildings on October 2, 1923

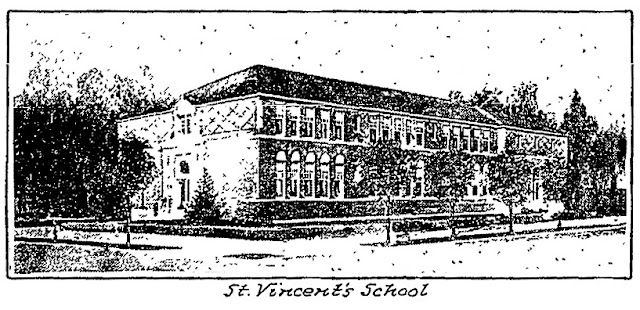

- The archdiocese hired architect Albert C. Martin to replace 507 in 1923 with the two-story, 99-by-113-foot brick St. Vincent's School. Its long side faced Flower Street. The school was demolished in 1953 to make way for the Harbor/110 Freeway, which opened through vanished parlors and classrooms on March 27, 1956. The school, as had the house, lasted only about 30 years; the freeway has been in place more than twice as long

|

| Above and at top are two morning views of the Hughes house taken in front of 421 West Adams, circa 1900. While Adams (left) and Flower streets remain unpaved, curbs and sidewalks have been installed, and in the case of 421, low concrete fencing of a type often seen fronting large houses in turn-of-the-century suburban Los Angeles. A horse block is seen at 421's curb; these were another feature frequently found among the street furniture of high-end neighborhoods, often etched with the surnames of the owners of the houses they served. |